ephor: Difference between revisions

Ὑγίεια καὶ νοῦς ἀγαθὰ τῷ βίῳ δύο (πέλει) → Vitae bona duo, sanitas, prudentia → Zwei Lebensgüter sind Gesundheit und Verstand

(CSV4) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<b class="b2">Be ephor</b>, v.: P. ἐφορεύειν. | <b class="b2">Be ephor</b>, v.: P. ἐφορεύειν. | ||

}} | }} | ||

==Wikipedia EN== | |||

The ephors were leaders of ancient Sparta and shared power with the two Spartan kings. The ephors were a council of five elected annually who swore "on behalf of the city", while the kings swore for themselves. | |||

Herodotus claimed that the institution was created by Lycurgus, while Plutarch considers it a later institution. It may have arisen from the need for governors while the kings were leading armies in battle. The ephors were elected by the popular assembly, and all citizens were eligible for election. They were forbidden to be reelected. They provided a balance for the two kings, who rarely cooperated with each other. Plato called the ephors tyrants who ran Sparta as despots, while the kings were little more than generals. Up to two ephors would accompany a king on extended military campaigns as a sign of control, and they held the authority to declare war during some periods in Spartan history. There were a total of 7 Ephors, consisting of the two kings and the 5 who were elected. | |||

According to Plutarch, every autumn, at the crypteia, the ephors would pro forma declare war on the helot population so that any Spartan citizen could kill a helot without fear of blood guilt. This was done to keep the large helot population in check. | |||

The ephors did not have to kneel down before the Kings of Sparta and were held in high esteem by the citizens, because of the importance of their powers and because of the holy role they earned throughout their functions. Since decisions were made by majority vote, this could mean that Sparta's policy could change quickly, when the vote of one ephor changed. (E.g. in 403 BC when Pausanias convinced three of the ephors to send an army to Attica; this was a complete turn around to the politics of Lysander.) | |||

Cleomenes III abolished the ephors in 227 BC, but they were restored by the Macedonian king Antigonus III Doson after the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC. Although Sparta fell under Roman rule in 146 BC, the position existed into the 2nd century AD, when it was probably abolished by the Roman emperor Hadrian and superseded by Imperial governance as part of the province of Achaea. | |||

Revision as of 12:56, 9 April 2019

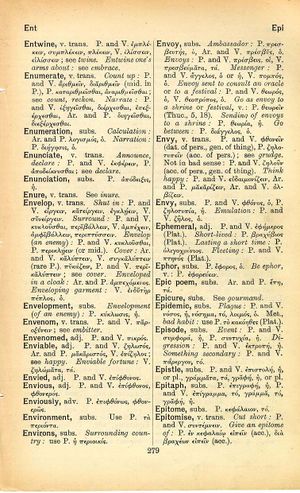

English > Greek (Woodhouse)

subs.

P. ἔφορος, ὁ. Be ephor, v.: P. ἐφορεύειν.

Wikipedia EN

The ephors were leaders of ancient Sparta and shared power with the two Spartan kings. The ephors were a council of five elected annually who swore "on behalf of the city", while the kings swore for themselves.

Herodotus claimed that the institution was created by Lycurgus, while Plutarch considers it a later institution. It may have arisen from the need for governors while the kings were leading armies in battle. The ephors were elected by the popular assembly, and all citizens were eligible for election. They were forbidden to be reelected. They provided a balance for the two kings, who rarely cooperated with each other. Plato called the ephors tyrants who ran Sparta as despots, while the kings were little more than generals. Up to two ephors would accompany a king on extended military campaigns as a sign of control, and they held the authority to declare war during some periods in Spartan history. There were a total of 7 Ephors, consisting of the two kings and the 5 who were elected.

According to Plutarch, every autumn, at the crypteia, the ephors would pro forma declare war on the helot population so that any Spartan citizen could kill a helot without fear of blood guilt. This was done to keep the large helot population in check.

The ephors did not have to kneel down before the Kings of Sparta and were held in high esteem by the citizens, because of the importance of their powers and because of the holy role they earned throughout their functions. Since decisions were made by majority vote, this could mean that Sparta's policy could change quickly, when the vote of one ephor changed. (E.g. in 403 BC when Pausanias convinced three of the ephors to send an army to Attica; this was a complete turn around to the politics of Lysander.)

Cleomenes III abolished the ephors in 227 BC, but they were restored by the Macedonian king Antigonus III Doson after the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC. Although Sparta fell under Roman rule in 146 BC, the position existed into the 2nd century AD, when it was probably abolished by the Roman emperor Hadrian and superseded by Imperial governance as part of the province of Achaea.