lictor

εἰς τὴν ἀγορὰν χειροτονεῖτε τοὺς ταξιάρχους καὶ τοὺς φυλάρχους, οὐκ ἐπὶ τὸν πόλεμον → you elect taxiarchs and phylarchs for the marketplace not for war

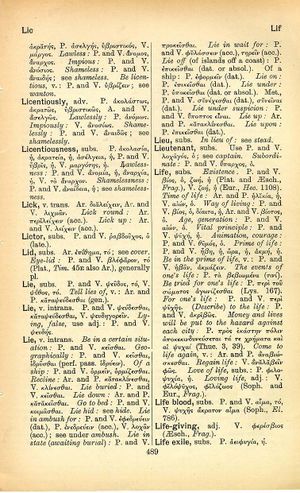

English > Greek (Woodhouse)

subs.

P. and V. ῥαβδοῦχος, ὁ (late.).

Latin > English (Lewis & Short)

lictor: (pronounced līctor, Gell. 12, 3, 4), ōris, m. 1. ligo; cf. Gell. 12, 3, 1 sqq.,

I a lictor, i. e. an attendant granted to a magistrate, as a sign of official dignity. The Romans adopted this custom from the Etrurians: Romulus cum cetero habitu se augustiorem tum maxime lictoribus duodecim sumptis (a finitima Etruria) fecit, Liv. 1, 8. The lictors bore a bundle of rods, from which an axe projected. Their duty was to walk before the magistrate in a line, one after the other; to call out to the people to make way (submovere turbam); and to remind them of paying their respects to him (animadvertere, v. h. v.). The foremost one was called primus lictor: apud quem primus quievit lictor, Cic. Q. Fr. 1, 1, 7, § 21; the last and nearest to the consul, proximus lictor, Liv. 24, 44 fin. The lictors had also to execute sentences of judgment, to bind criminals to a stake, to scourge them, and to behead them, Liv. 1, 26; 8, 7; 38; 26, 16.—It was necessary that lictors should be freeborn: not till the time of Tacitus were freedmen also appointed to the office. They were united into a company, and formed the decuriae apparitorum (public servants). In Rome they wore the toga, in the field the sagum, in triumphal processions a purple mantle and fasces wreathed with laurel: togulae lictoribus ad portam praesto fuerunt, quibus illi acceptis, sagula rejecerunt et catervam imperatori suo novam praebuerunt, Cic. Pis. 23, 55. Only those magistrates who had potestatem cum imperio had lictors. In the earliest times the king had twelve; immediately after the expulsion of the kings, each of the two consuls had twelve; but it was soon decreed that the consuls should be preceded for a month alternately by twelve lictors, Liv. 2, 1; a regulation which appears to have been afterwards, although not always, observed, Liv. 22, 41; Cæsar was the first who restored the old custom, Suet. Caes. 20.—The decemvirs had, in their first year of office, twelve lictors each one day alternately, Liv. 3, 33; in their second year each had twelve lictors to himself, id. 3, 36.— The military tribunes with consular power had also twelve lictors, Liv. 4, 7; and likewise the interrex, id. 1, 17.—The dictator had twenty-four, Dio, 54, 1; Polyb. 3, 87; Plut. Fab. 4; the magister equitum only six, Dio, 42, 27. The praetor urbanus had, in the earlier times, two lictors, Censor. de Die Natal. 24: at enim unum a praetura tua, Epidice, abest. Ep. Quidnam? Th. Scies. Lictores duo, duo viminei fasces virgarum, Plaut. Ep. 1, 1, 26; in the provinces he had six; but in the later times the praetor had in the city, as well as in the province, six lictors, Polyb. 3, 40: cum praetor lictorem impellat et ire praecipitem jubeat, Juv. 3, 128. The quaestor had lictors only in the province, when he, in consequence of the praetor's absence or death, performed the functions of propraetor, Sall. C. 19; Cic. Planc. 41, 98. Moreover, the flamen dialis, the vestals, and the magistri vicorum had lictors; these, however, appear to have had no fasces, which was also the case with the thirty lictores curiati (who summoned the curiae to vote), Cic. Agr. 2, 12, 81; Gell. 15, 27, 2; Inscr. Grut. 33, 4; 630, 9.—

II Transf.: lictorem feminae in publico unionem esse, a lady's mark of distinction, Plin. 9, 35, 56, § 114.